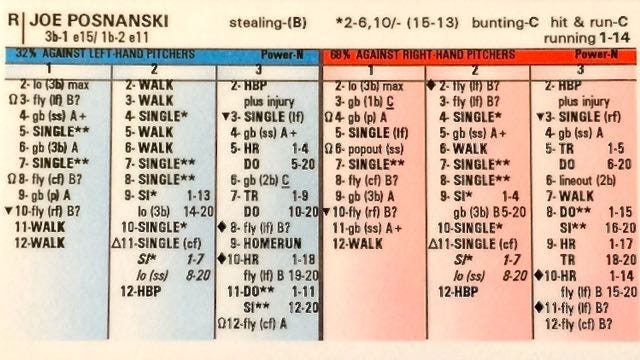

Strat-o-Matic was not the first tabletop baseball game I ever played. No, first was this game called "Statis Pro Baseball," which was this fantastic little baseball card game invented by an Iowa newspaper columnist and, later, sports gambling guru named Jim Barnes. There are two things I remember most about the game:

1. Unlike Strat-o-Matic, where hitter…