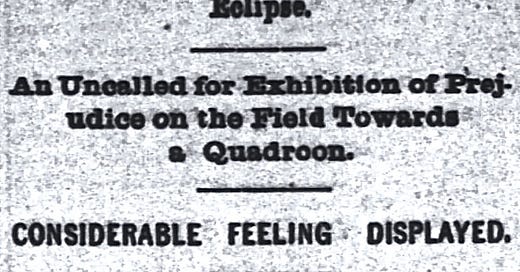

Shadowball 99: Cap Anson and Fleet Walker

This is a free preview for JoeBlogs. This is part of the Shadowball 100, which will include 100 of the most fascinating, awesome, real and fictional players in baseball history. This series corresponds with the Baseball 100, a rundown of the 100 greatest Major League Baseball players ever. To sign up for JoeBlogs, you can become a member here.

* * *

Here…