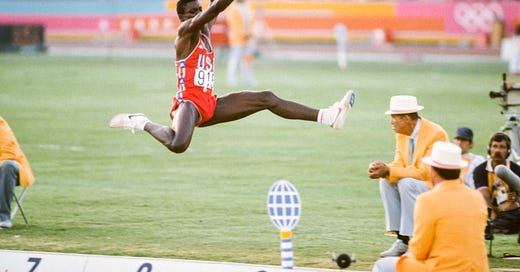

Sometimes, you get lucky. Back in 2011, for some reason, I was given the opportunity to talk with Carl Lewis. It was about the Hershey’s Track and Field Championship; he was the spokesperson.

Note to young writers: When you get a chance to talk with a remarkable person in any field, even if it’s not on a topic that you find especially compelling, take th…