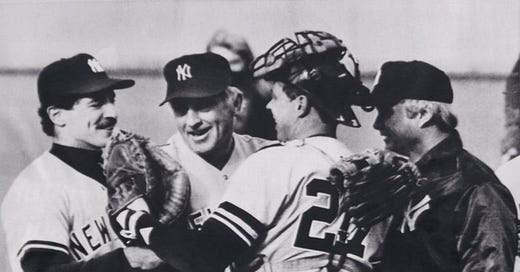

Baseball 79: Phil Niekro

Phil Niekro went to bed on Oct. 5, 1985 conflicted and unsure about what he would do the next day. His Yankees had just lost to Toronto 5-1, and that essentially ended New York's season. They had entered this final three-game series trailing the Blue Jays by three games in the American League East. A sweep could have forced a one-game playoff, and New Y…