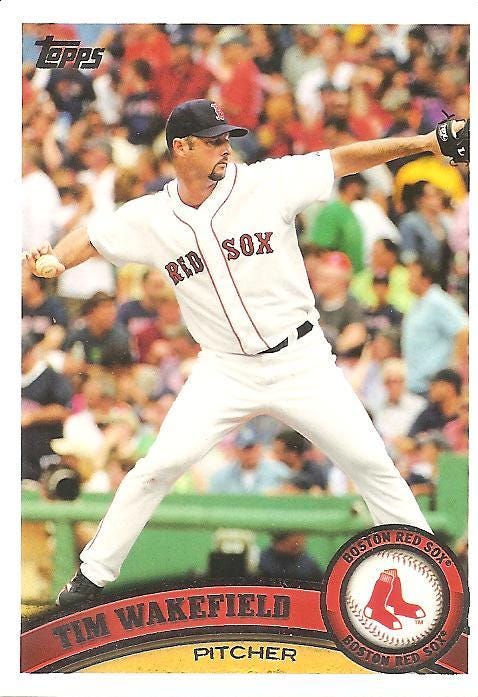

Ballot 23: Tim Wakefield

Tim Wakefield

Played 19 years for two different teams

All-Star won exactly 200 games in his career 34.5 WAR, 3.9 WAA

Pro argument: Great knuckleball pitcher of his time.

Con argument: His knuckleball got hit a lot.

Deserves to be in Hall?: No

Will get elected this year?: No

Will ever get elected?: No.

* * *

Knuckleballs are the closest thing to witchcraft that I…