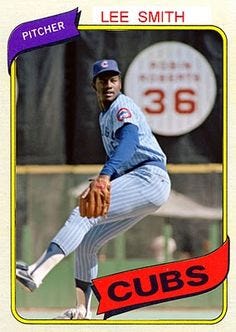

Ballot 18: Lee Smith

Lee Smith

Played 18 years for eight teams

Seven-time all-star led the league in saves four times. 29.4 WAR, 13.8 WAA

Pro argument: Great reliever who for 13 years held the all-time saves record.

Con argument: Closers are specialists who pitch a fraction of innings that starters do.

Deserves to be in Hall?: Depends on your thought on relievers.

Will get electe…